Last week a judge in Rock Hill, South Carolina, vacated the convictions of the “Friendship Nine,” a group of African American men who protested segregation at a sit-in in 1961. The group gained nationwide notoriety for electing to serve jail time rather than pay a fine, giving the civil rights movement a new tactic known as “jail, no bail” to fight segregation peacefully.

Civil rights protestors’ convictions vacated 54 years later

Fifty-four years ago, on Jan. 31, 1961, a group of young African American men protested segregation by sitting down at the whites-only counter at McCrory’s five-and-dime store in Rock Hill. They were arrested for trespassing and breach of the peace and were taken to prison.

The men were convicted and ordered to pay a $100 fine or spend 30 days in jail. One man in the group, Charles Taylor, paid his bail and was released. The other nine, dubbed the Friendship Nine because eight of them attended nearby Friendship Junior College, did not post bail but instead served their jail term.

Eight of the nine are still alive today, and seven were in the Rock Hill courthouse last Wednesday to see their convictions vacated almost 54 years later to the day. The eighth surviving member, Thomas Walter Gaither, sent his son in his place. When a conviction is vacated, it is as if the original trial and verdict never happened.

The men were also reunited with attorney Ernest A. Finney Jr., who defended them in the 1961 case. Finney went on to become chief justice of the South Carolina Supreme Court in 1994, making him the first African American to hold that title since Reconstruction.

‘Jail, no bail’ policy invigorated civil rights movement

When the Friendship Nine held their sit-in at McCrory’s in early 1961, the civil rights movement was still relatively new. It would be another two years before Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech and four years before the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was signed into law. Sit-ins had started the year before in 1960 in Greensboro, North Carolina, and had spread throughout the South.

But the sit-in of the Friendship Nine gained national notoriety because of the group’s refusal to pay bail, a stance they maintained even when the NAACP offered to help. Instead, they served their sentence, 30 days of hard labor on a chain gang, as part of their “jail, no bail” strategy.

“Jail, no bail” became a new tactic in nonviolent protests. It showed the nation that protestors were serious and committed to the cause. It also took the financial onus off civil rights groups like the NAACP. Instead of paying fines benefiting a system that upheld segregation, the new strategy forced that system to spend money feeding and housing the imprisoned protestors.

The strategy was also important to the student-led civil rights organization the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, a group whose name later changed to the Student National Coordinating Committee. Inspired by sit-ins in Greensboro and elsewhere, the group was founded in April 1960 with the goal of organizing similar protests, including sit-ins and freedom rides. The group did not have the funds to bail every protestor out of jail, so the commitment to stay in prison was crucial to their existence.

Legacy of the Friendship Nine lives on

The Friendship Nine sit-in was one of many protests in the early 1960s, but it had a significant effect on the civil rights movement at the time, and its legacy lives on.

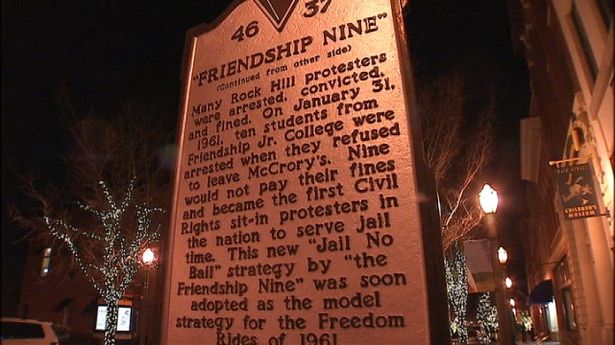

In 2007, the city of Rock Hill put up a historic marker on E. Main Street to commemorate the event and honor the men: John Gaines, Thomas Gaither, Clarence Graham, W.T. “Dub” Massey, Willie McCleod, James Wells, David Williamson Jr., Mack Workman and Robert McCullough, who died in 2006.

The restaurant that now stands where McCrory’s stood over half a century ago, Old Town Bistro, also honored the men by engraving their names on the stools.

In the proceedings last week, the prosecutor representing the state offered “heartfelt apologies” for what happened in 1961. Circuit Judge John C. Hayes III, who happens to be the nephew of the judge in the original 1961 case, echoed that regret, saying, “We cannot rewrite history, but we can right history.”

Photos: WSOC-TV

Related:

1 comment

Daisy

I really like this article. Thank you for publishing this story. I do wish it included information about the children's author that spearheaded the efforts to vacate the sentences of the Friendship 9. Her name is Kimberly P. Johnson and she wrote "No Fear For Freedom: The Story of the Friendship 9", published in March 2014. Johnson gained invaluable information from a camp hosted annually by Dr. Bernice King, last living daughter of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. during the summer of 2014. She then took that information to the Deputy Solicitor and 16th Circuit Solicitor in Rock Hill and York, South Carolina. It was a collaborative effort that allowed the momentous event to occur. Just wish more people knew how it all happened. Thank you again for your time to share this story!